Dwarfism remains one of the least understood forms of disability in Rwanda. While persons with dwarfism are part of our communities living, working, learning, and contributing to society they continue to face widespread misconceptions, stigma, and systemic barriers. Improving public understanding is a crucial step toward promoting dignity, inclusion, and equal rights. As noted by Honorine TUYISHIMIRE, Executive Director of RULP, “Limited awareness continues to expose persons with dwarfism to discrimination and stigma, yet understanding is the foundation of respect and inclusion.”

What is Dwarfism?

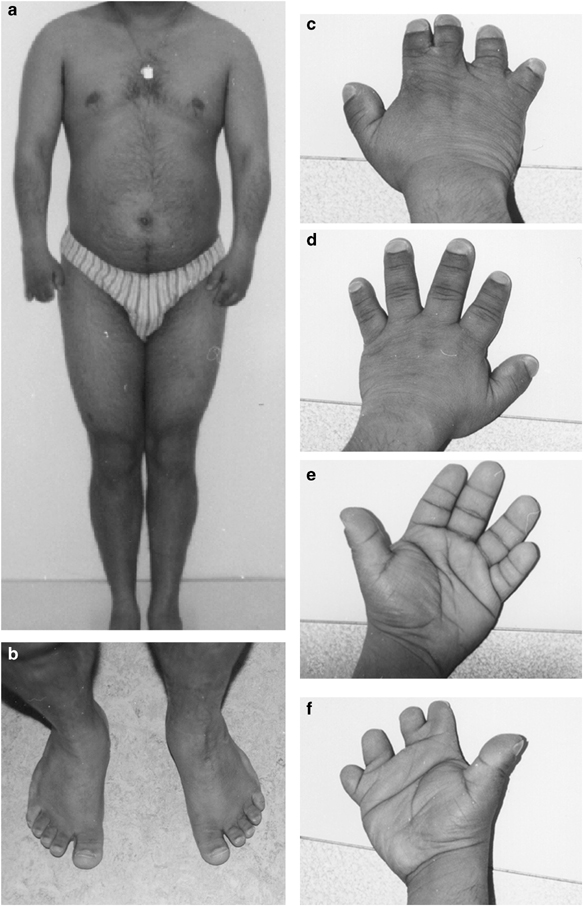

According to the Mayo Clinic, dwarfism is a medical condition characterized by short stature, usually defined as an adult height of 147 cm (4 feet 10 inches) or below. It is most often caused by genetic or medical factors affecting bone growth, such as achondroplasia, which is the most common type. Dwarfism is not a disease, nor is it contagious. Persons with dwarfism have normal intelligence and are capable of living full, independent, and productive lives when barriers are removed.

In Rwanda, persons with dwarfism are legally recognized under the broader category of persons with disabilities and are entitled to equal rights and protections under national laws and international human rights instruments.

“Legal recognition must go hand in hand with practical inclusion,” emphasizes Honorine, “because rights on paper alone do not change lived realities.”

Common myths and misconceptions

Despite clear medical explanations, many myths about dwarfism still exist in Rwandan communities. One common belief is that dwarfism is a curse or punishment linked to superstition or family wrongdoing. This belief is incorrect. Dwarfism is a natural medical condition, usually caused by genetic or growth-related factors. It is not contagious, not a result of witchcraft, and not caused by the actions of parents or families. Such misconceptions often lead to stigma, shame, and exclusion of persons with dwarfism from community life.

According to Honorine, “When communities associate dwarfism with superstition, they deny individuals’ dignity and expose them to lifelong discrimination.”

Another deeply harmful myth is the belief that persons with dwarfism cannot have intimate relationships, give birth, or form families. In some communities, they are wrongly perceived as sexless or incapable of reproduction. This misconception is medically and socially inaccurate. Persons with dwarfism have the same reproductive rights and capacities as other adults, and many are parents, spouses, and caregivers. Such beliefs deny them their humanity, expose them to social exclusion, and increase the risk of sexual rights violations, including denial of marriage, family life, and reproductive health services.

As emphasized by Honorine, “Denying the sexuality and reproductive rights of persons with dwarfism is a form of dehumanization. They have the same right to love, family, and parenthood as any other person.”

Another widespread myth is that persons with dwarfism cannot study or work. In reality, persons with dwarfism have the same intellectual abilities as others and can succeed in school, employment, leadership, and business when given equal opportunities. The main challenges they face come from negative attitudes, inaccessible infrastructure, and lack of reasonable accommodation not from their condition.

“Ability is not defined by height,” she stresses, “but by opportunity, support, and an inclusive environment.”

There is also a harmful belief that persons with dwarfism should be hidden or treated with pity. This approach denies them dignity and reinforces discrimination. Persons with dwarfism do not need charity or sympathy; they need respect, inclusion, and recognition of their rights. Like all citizens, they deserve to participate fully in family, community, and national development.

“Pity is not protection,” She notes, “rights, respect, and participation are what truly empower persons with dwarfism.”

Lived realities of Persons with Dwarfism in Rwanda

The daily experiences of persons with dwarfism in Rwanda reveal both resilience and persistent challenges. Social attitudes remain a major barrier, with many individuals facing ridicule, name-calling, or intrusive staring in public spaces. Such experiences affect self-esteem and mental well-being, particularly among children and youth.

“Discrimination often begins with words and attitudes, but its impact lasts a lifetime,” explains Honorine.

Access to services is another challenge. Public infrastructure such as transport, offices, schools, and health facilities is often designed without considering the needs of persons with short stature. Simple tasks like reaching service counters, using public transport, or accessing sanitation facilities can become daily obstacles.

According to Honorine, “Inclusive infrastructure is not a luxury; it is a basic requirement for equal access to services.”

Economic exclusion is widespread, with many persons with dwarfism experiencing unemployment due to discrimination and negative employer attitudes. Even when qualified, they are often overlooked for job opportunities.

“Economic inclusion is central to dignity and independence,” She says” no one should not be included from work because of physical appearance.”

Strength, resilience, and agency

Despite these challenges, persons with dwarfism in Rwanda continue to demonstrate remarkable strength and resilience. Many are active advocates, parents, professionals, and community leaders who challenge stereotypes and demand inclusion. Organizations led by and for persons with dwarfism play a critical role in raising awareness, supporting economic empowerment, and engaging duty bearers.

“Persons with dwarfism are not passive beneficiaries; they are leaders and agents of change,” affirms Honorine

International Human Rights Standards

International human rights conventions clearly affirm the rights of persons with disabilities including persons with dwarfism to family life, sexuality, and reproduction.

The CRPD explicitly protects these rights. Article 23 (Respect for home and the family) states that persons with disabilities have the right “to marry and to found a family on the basis of free and full consent of the intending spouses,” and that States Parties shall ensure “the rights of persons with disabilities to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children.” This provision directly refutes the myth that persons with dwarfism cannot or should not have children.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) further affirms this principle. Article 16 provides that “men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family.” Disability, including dwarfism, is not a lawful ground for denying these rights.

Similarly, the ICCPR recognizes the right to family life. Article 23 states that “the family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.” Excluding persons with dwarfism from family life based on myths or stigma is therefore a violation of this fundamental protection.

The ICESCR reinforces these protections by recognizing the right to the highest attainable standard of health, including sexual and reproductive health. Article 12 obliges States to ensure access to health services without discrimination covering maternal health, reproductive health information, and family planning services for persons with disabilities.

As emphasized by Honorine “When society denies the sexuality and reproductive rights of persons with dwarfism, it violates not only their dignity but also clear international human rights standards that Rwanda has committed to uphold.”

The way forward: Building an inclusive Rwanda

Creating a society that respects and includes persons with dwarfism requires collective and sustained effort from government institutions, civil society organizations, communities, and individuals. Inclusion must be intentional and guided by a rights-based approach.

As Honorine concludes, “An inclusive Rwanda is one where persons with dwarfism are seen, heard, and valued—not as exceptions, but as equal citizens.”

She continued saying that public awareness is a critical starting point. Continuous education at community, school, and media levels is necessary to dispel myths and misinformation about dwarfism. Accurate information helps challenge stigma, promotes respectful attitudes, and fosters acceptance of diversity. When communities understand dwarfism as a natural medical condition, discrimination and harmful practices are significantly reduced.

In addition, inclusive planning is equally important. Public infrastructure and social services must be designed to accommodate diverse body types, including persons with short stature. This includes accessible public transport, buildings, service counters, sanitation facilities, and communication systems. Inclusive design ensures that persons with dwarfism can access services independently and participate fully in public life.

“Economic inclusion is a key pillar of dignity and independence. Promoting equal employment opportunities, skills development, and entrepreneurship for persons with dwarfism is essential. Employers should be encouraged to provide reasonable accommodation and to assess individuals based on their abilities and qualifications rather than physical appearance. Economic empowerment reduces dependency and strengthens social inclusion. She insisted.

In conclusion, a rights-based approach must guide all efforts toward inclusion. Rwanda has laws and policies that protect the rights of persons with disabilities, but effective implementation remains crucial. Ensuring that these legal frameworks are enforced, monitored, and adequately resourced will help translate commitments into real change in the lives of persons with dwarfism. “Understanding dwarfism is not only about knowledge it is about recognizing humanity, dignity, and rights. An inclusive Rwanda is one where persons with dwarfism are seen, heard, and valued as equal members of society” She concluded.